by Anna Alberati

Profane cantatas and baroque images

The Casanatense Library preserves among its most precious and rare collections a collection of manuscripts that are very important for the history of music, in particular for the history of Roman music around the middle of the seventeenth century. It is about twenty manuscripts in which several profane vocal compositions that can be defined as Chamber Cantatas have been transcribed by various copyists. They are compositions by “Roman” musicians, almost all with a single-voice ensemble, the Soprano voice, with the accompaniment of the basso continuo.

The Casanatense Library preserves among its most precious and rare collections a collection of manuscripts that are very important for the history of music, in particular for the history of Roman music around the middle of the seventeenth century. It is about twenty manuscripts in which several profane vocal compositions that can be defined as Chamber Cantatas have been transcribed by various copyists. They are compositions by “Roman” musicians, almost all with a single-voice ensemble, the Soprano voice, with the accompaniment of the basso continuo.

This series of manuscripts is part of the fundamental nucleus of the Music Section of the Casanatense Library, or the Baini Fund, the private musical collection of Giuseppe Baini that arrived in the Library as a donation by testamentary bequest in the year 1844.

In addition to carrying out activities as a singer and then as chamberlain of the Sistine Chapel, Baini was an illustrious scholar. He fits into that particular historical moment, the end of the 18th and the first half of the 19th century, which saw the emergence of the first great works of musical historiography and the action of a generation of scholars who were also bibliophiles, researchers of sources and documents as well as collectors themselves. They became the initiators of modern musicology, a discipline that would be configured as a true science of the historical-philological organization of sources.

It is not difficult to imagine Giuseppe Baini frequenting the numerous Roman bookshops of the late 18th and early 19th centuries in search of musical sources, old editions, ancient manuscripts, books not only useful for his studies dedicated to Pierluigi da Palestrina, but also beautiful, with printed or transcribed music far from his time and perhaps (or certainly) from his taste, but which the singer-scholar jealously preserves in his bookcase, like precious jewels.

These manuscripts were written in a period that can be dated to the mid-17th century, between 1640 and 1670, perhaps up to 1680-1690, and although they are different, they present some common characteristics: they contain compositions of the same musical genre, that is, sung by one voice with the accompaniment of the basso continuo; the composers are all musicians active in Rome in the same period; the volumes have a very similar material physiognomy, because they are oblong in format with dimensions of approximately 100×270 millimetres; the copyists are always the same ones who are used in the transcription of the various cantatas.

These manuscripts were written in a period that can be dated to the mid-17th century, between 1640 and 1670, perhaps up to 1680-1690, and although they are different, they present some common characteristics: they contain compositions of the same musical genre, that is, sung by one voice with the accompaniment of the basso continuo; the composers are all musicians active in Rome in the same period; the volumes have a very similar material physiognomy, because they are oblong in format with dimensions of approximately 100×270 millimetres; the copyists are always the same ones who are used in the transcription of the various cantatas.

The differences instead concern the binding and the ornamentation: while some have a simple binding in soft or semi-rigid parchment, others, instead, are very luxurious manuscripts, with a binding in red morocco that features a decoration made of ornamental elements impressed in gold on the leather. Some also have coats of arms, heraldic insignia of noble families impressed in gold on both sides of the binding.

As a musicologist from a few decades ago, John Glenn Paton, said, the first sight of some of these books take a person’s breath away, so handsome are their leither.

Looking at the bindings, in particular, the idea arises that this type of musical manuscript was created not only for private use (since the cantatas were performed in a domestic environment, that is, the halls of aristocratic residences), but also to be a gift from the noble master of the house to his guests or even a wedding gift: the coats of arms present in this collection, in fact, are of a feminine nature, and seem to support the reality of this last hypothesis.

Furthermore, these manuscripts of collections of cantatas (which are preserved, in large numbers, scattered in many libraries in Italy and Europe and which have very few printed counterparts), reveal a precise attention towards music, which seems to be considered not only for a practical use, but on the contrary appears worthy of preservation as a prestigious testimony. As for the ornamentation, the initials of each cantata are almost always embellished with graphic motifs, with one exception, which concerns Ms. 2478.

As for the ornamentation, the initials of each cantata are almost always embellished with graphic motifs, with one exception, which concerns Ms. 2478.

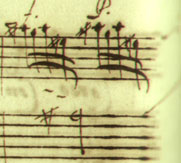

In many manuscripts, in fact, the initial letters, relative to the incipit of the literary text, are often large and decorated with refined pen strokes, while in one of them, but only one, Ms. 2478, on the opening page of each of the 28 cantatas the musical and vocal text is preceded-flanked by elegant images drawn with sepia-colored ink, the same as the musical writing.

They are small vignettes of 70×80 millimetres, enclosed in a simple frame, delicate and very fine pen drawings with different subjects, unrelated to the text of the cantata they introduce. These subjects range from mythological subjects to a picture of country or city life, in a city that is easy to recognise as Rome and in it very well-known places such as Piazza Navona, Piazza Colonna, Via del Corso. The place of origin of these manuscripts is undoubtedly Rome, the city where, between 1620 and 1640, this new genre of music was born.  Together with the opera in music (in the theatre) and the musical oratorio (in the church), the cantata is one of the great new musical forms: whether profane, spiritual or sacred, with a generic expression, which defines the environment for which the cantata is intended, it will also be called cantata da camera (or per camera).

Together with the opera in music (in the theatre) and the musical oratorio (in the church), the cantata is one of the great new musical forms: whether profane, spiritual or sacred, with a generic expression, which defines the environment for which the cantata is intended, it will also be called cantata da camera (or per camera).

In the Roman musical world, artists collected and developed the seeds of the new recitative style born in Florence and of the cantata genre that emerged in Venice. And in the city of the Pope, the new genre developed marvelously, especially thanks to the rich and varied aristocracy (Barberini, Borghese, Pamphili, Colonna, Rospigliosi), who supported and listened with delight to the numerous and very active singer-musicians and composers of cantatas. To use the words of Nino Pirrotta, the cantata, born and baptized in Venetian soil, would rise to a definite art form in Rome.

The term cantata was first used in 1620 by Alessandro Grandi in his Cantate ed Arie a voce sola, but later the free form of the madrigal, combined with a taste for the dramatic genre, produced a completely new genre, an intimate music for solo voices.

Usually accompanied by the continuo alone, the vocal parts (rarely more than three, but usually just one) alternated the recitative style with the lyrical one, thus reflecting the passage from the narrative to the emotional moment. There were no fixed rules for the duration or the number of arias that had to contribute to form the cantata, so examples can be found with a single aria or with multiple arias, or with arias alternating with the recitative style.

In the seventeenth century the cantata took the place that in the sixteenth century was occupied by the madrigal. The fundamental factors underlying its affirmation were the aspiration of music to erect itself into great sound architectures; the pressing progress of the dramatic spirit; the progressive acquisition of instruments for the voices, that is, the opening of the era of vocal music accompanied by instruments and the birth of the doubling of the lowest voice among those that sing during the pauses of the bass (together with the bass part), that is, the basso continuo, which served the instrumentalist who accompanied the voices with the organ, the harpsichord or the lute. Finally, the tendency to exalt the upper voice of the polyphonic composition, that is, the cantus.

In the seventeenth century the cantata took the place that in the sixteenth century was occupied by the madrigal. The fundamental factors underlying its affirmation were the aspiration of music to erect itself into great sound architectures; the pressing progress of the dramatic spirit; the progressive acquisition of instruments for the voices, that is, the opening of the era of vocal music accompanied by instruments and the birth of the doubling of the lowest voice among those that sing during the pauses of the bass (together with the bass part), that is, the basso continuo, which served the instrumentalist who accompanied the voices with the organ, the harpsichord or the lute. Finally, the tendency to exalt the upper voice of the polyphonic composition, that is, the cantus.

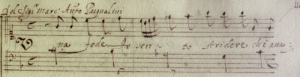

The 28 cantatas transcribed in Ms. 2478, in addition to 2 anonymous ones, are composed by the following musicians: Giacomo Carissimi (2 cantatas), Venanzio Leopardi (1), Arcangelo Lori (1), Giovanni Marciani (3), Marc’Antonio Pasqualini (11), Giovanni Carlo Rossi (1), Luigi Rossi (4), Mario Savioni (2), Piero Antonio Vanini (1).

Among these musicians, Luigi Rossi and Giacomo Carissimi are of great importance and absolute artistic value, authors of a large number of cantatas.

Luigi Rossi, born in Torremaggiore (Foggia) around 1598, was a composer, organist, lutenist and singer: he spent almost all his life in Rome, first in the service of Marco Antonio Borghese, Prince of Sulmona, then as organist at S. Luigi dei Francesi; in 1641 he was hired by Cardinal Antonio Barberini as a chamber virtuoso and when the Barberinis fell into disgrace (due to the election of Pope Innocent X) he was in Paris between 1644 and 1647, gaining international fame. He then returned to Rome, where he died in 1653.

Giacomo Carissimi, born in Marino (Rome) in 1605, was the choirmaster of the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in the German-Hungarian College from 1630, where he remained for 44 years, until his death; although invited and requested by various important figures (kings and emperors), he always remained in Rome, where he was also appointed “Choirmaster of the chamber concert” by Christina of Sweden.

He spent his life as a teacher in the Chapel of S. Apollinare annexed to the basilica, a composer of music commissioned by the Archconfraternity of the SS. Crocifisso for its oratory, but he was also a private teacher for the numerous students who came from Italy and Europe and who spread his fame throughout Europe (Christoph Bernhard, Kaspar Kerll, Johann Philipp Krieger, Antonio Maria Abbatini, Bernardo Pasquini, Marc-Antoine Charpentier).

Alongside these two stars of the Roman cantata of the seventeenth century (and not only), there is Marc’Antonio Pasqualini, (known as Streviglio), (Rome 1614-1691), a composer and soprano of great fame, who, after being a child singer at S. Luigi dei Francesi, went into the service of Cardinal Barberini.

Arcangelo Lori (Arcangelo del Leuto), (Rome 1611-1679), organist and archlute player at S. Luigi dei Francesi, active for the major solemnities of the Roman churches.

Finally Mario Savioni (Rome, 1608-1685), composer and singer (sopranist and then contralto) in the Sistine Chapel.

All the cantatas, in their alternation between recitatives and arias, have the same passionate subject: love.