In 1987, a large iconographic exhibition entitled In Praesepio: images of the Nativity in engravings from the 16th-19th centuries was set up in Casanatense, curated by Iolanda Olivieri and Angela Vicini Mastrangeli.

On that occasion, 300 prints taken from the Casanatense collection were exhibited, the subject of which was attributable to one of the four salient moments identified for the occasion within the iconography of Christmas: Announcement to the Shepherds, Nativity, Adoration of the Shepherds, Adoration of the Magi. In the following years some of these prints were shown to the public again in exhibitions of lesser importance and richness.

This year, with Casanatense also participating in the national event promoted by MiBACT Christmas Cards, from this large “Christmas corpus” we wanted to isolate two themes, perhaps of less importance within the great iconography generated by the narration of the New Testament, but without any doubt the evangelical message and the popular Christian tradition are the foundations, in particular that of the Nativity Scene: the Announcement to the Shepherds and the Adoration of the Shepherds, the first witnesses of the miraculous event.

This year, with Casanatense also participating in the national event promoted by MiBACT Christmas Cards, from this large “Christmas corpus” we wanted to isolate two themes, perhaps of less importance within the great iconography generated by the narration of the New Testament, but without any doubt the evangelical message and the popular Christian tradition are the foundations, in particular that of the Nativity Scene: the Announcement to the Shepherds and the Adoration of the Shepherds, the first witnesses of the miraculous event.

The presence of the shepherds and the angelic announcement to them belong to the context of the Gospel of Luke (Luke, 2.8 and following) and contain a clear reference to the predilection of this evangelist for the poor, the disinherited of the earth and the sinners and therefore to the coming of the Savior for them in the first place. Et pax in terra hominibus bonae voluntatis, men of good will who are certainly in every place and in every situation, but whom Christ seeks out in the poorest and most degraded contexts, we would say today.

It is useful to note that in the Casanatense collection of prints, the engravings on these themes are much more numerous than those displayed in the exhibition. A selection was made according to criteria of quality but also of originality: in fact some prints are on display not so much or not only for their intrinsic engraving or artistic value, but for the particularity of the iconographic system or for the “invention” little known or lost from which they descend.

The Library thanks the Dominican Fathers of Minerva for the kind loan of some pieces of their large Nativity scene, which warm up the setup of this exhibition.

The curators of the exhibition Sabina Fiorenzi and Barbara Mussetto

THE ANNOUNCEMENT TO THE SHEPHERDS

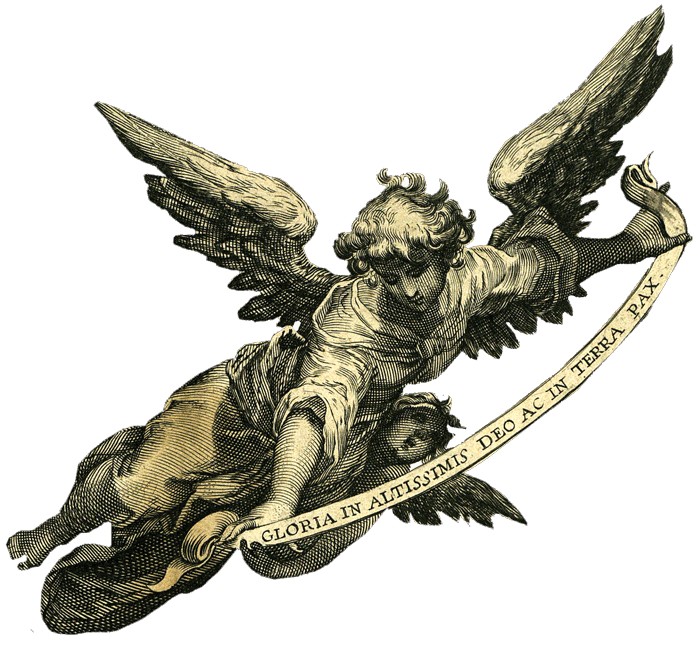

Luke’s evangelical account of this episode is full of visually striking narrative cues: the justified terror of the shepherds at the sight of the angel (An angel of the Lord appeared before them and the glory of the Lord surrounded them with light. They were greatly frightened ), his reassurances (Do not be afraid), the announcement of joy for the coming true of the prophecies and for the birth of the Savior (Behold, I bring you good news of a great joy, which will be for all the people: today he was born to you in the city of David a savior, who is the Lord Christ), the multitude of the celestial hosts that burst forth from above (And immediately a multitude of the celestial army appeared with the angel praising God and saying: «Glory to God in the highest heaven and peace on earth to the men he loves”). Despite this, the episode was almost unknown in sacred iconography until the 13th and 14th centuries and only began to be treated at the end of the 14th century, with the inclusion of shepherds who kneel away from the action in the foreground or who timidly enter in the main scene, looking out of a door or window.

But starting from the second half of the century. XVI the indications of the Council of Trent on devotional matters meant that this subject spread in a particular way due to its consolatory inspiration: the theme of the life of farmers and shepherds, poor, but comforted by the presence of God who becomes incarnate for them, it was also presented to the faithful as an example for them to accept their life condition with resignation. The shepherds thus became a fundamental element in all depictions of the Nativity, captured starting from the moment in which the archangel Gabriel announces the happy news to them. Normally the scene of the Announcement is strongly influenced by Luke’s narration: human figures and flocks emerge from the deep darkness while the sky explodes in a blinding light that pierces the clouds and puts men and herds to flight, scattering them in terror across the fields. From the night of sin to the blinding light of salvation, for the moment only announced by a messenger who speaks on behalf of God the Father, everyone is waiting to know who or what carries this promise.

These small, frightened men, whom the angel can barely reassure, in this first phase are often represented as simple figures, sometimes even scattered piecemeal across the landscape, almost a pretext for landscape representations of a rustic-pastoral genre. Alongside them there are animals, obviously sheep, lambs and rams in the first place, but then calves, dogs, cats and birds appear on the scene.

WORSHIP OF THE SHEPHERDS

Here the shepherds arrive in the presence of the Holy Family: true adoration makes its appearance towards the end of the 16th century, always following the new Tridentine catechistic-devotional indications. What were the shepherds looking for in the nativity scene (Quem quaeritis in nativity scene, pastores?) and who do they find there at the end of their frantic race in the night illuminated only by the flaming tail of the Comet and by their faith?

The Madonna, who from the end of the 13th century abandons the position lying on her side typical of oriental iconography, kneels in an adoring position. As described by St. Bridget who visited Bethlehem in 1370 and in her Revelations narrates her vision of the Virgin during and after the miraculous birth. It was precisely the Brigidine Revelations that took the place of the apocryphal Gospels as a source of iconographic inspiration for the representation of the Nativity.

St. Joseph, standing or sitting, often in a secluded position, sometimes with a lit candle in his hand, a detail also indicated by the Swedish mystic, who had described how the splendor of the Child, lying naked in the manger, obscured every other light present, including the light of the candle that St. Joseph held in his hand. This detail is frequently found in Flemish iconography, offering artists the opportunity for new and sometimes reckless luministic solutions.

The Baby Jesus, who progressively loses the tight swaddling, a memory or premonition of the tomb, ends up walking around completely naked, like any new born baby, placed free on the ground on the straw, on a corner of Mary’s mantle or inside the warmest manger. With his gaze fixed on his mother’s.

And what do our shepherds do? The moving and suspended sharing of the sublime and incomprehensible mystery of the divine birth that Mary and Joseph have just experienced together with their child is abruptly interrupted by the arrival of these men (and some rare women) with their small noisy animals in tow. They arrive fearful, hesitant, curious; they break the atmosphere of adoring meditation with a cumbersome presence, with awkward or dramatic gestures, with primitive sounds of instruments that imitate the bleating of sheep and lambs. They bring simple gifts – chickens, lambs, turkeys, pigs – a detail absent in the Gospels, inserted as an iconographic parallel to the subsequent and more precious offerings of the Magi. In addition to live animals, such as the lambs that we find lying on the shoulders of the shepherds or that docilely follow or precede them, as if competing to be the first to offer themselves to the Child, foodstuffs appear, most often contained in baskets, amphorae, baskets carried on the head, under the arm, in the hands of festive shepherdesses. Each of these offers has a naturalistic value but can also take on a symbolic one.

It is the first of Jesus’ epiphanies, entirely dedicated to the miserable and the outcasts, the humble and the simple: he was born only a few hours ago and already “denies himself” to his family, to offer himself to the world for which he became incarnate. Mary knows this and with a very sweet gesture of immense generosity, she lifts an edge of the sheet that wraps the Child, to show him in all that divine splendor that dazzles and tames men and animals, the entire creation. Giuseppe, standing aside, seems not to understand for now. He will understand and accept later, when angels and events put him face to face with the incredible extraordinary nature of a life – at times cruel – which, if he alone had been able to choose, perhaps he would never have asked to live. Sabina Fiorenzi