by Valeria Viscido

The Biblioteca Casanatense conserves 23 registers of readers, from February 1872 to October 1898, with Ms. Cas. 493/1-23: the registers pass through a decisive moment that joins the 20th century and, more recently, the present day. Looking more closely at the registers, from 1872 to 1880, it is possible to isolate on them a couple of handwritten notes, perhaps not particularly relevant, but able to tell part of the story of Italian library history, particularly Roman, in diachrony.

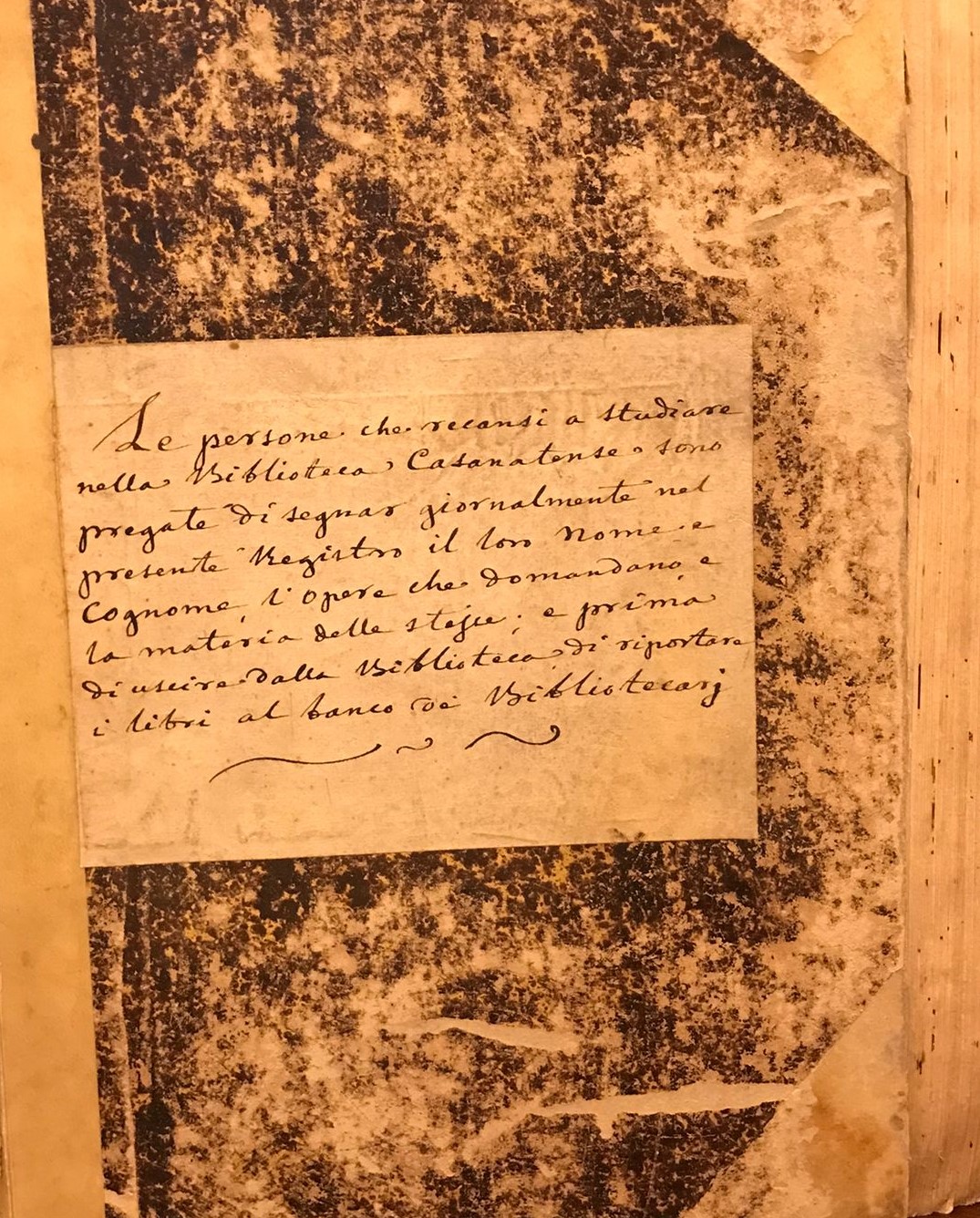

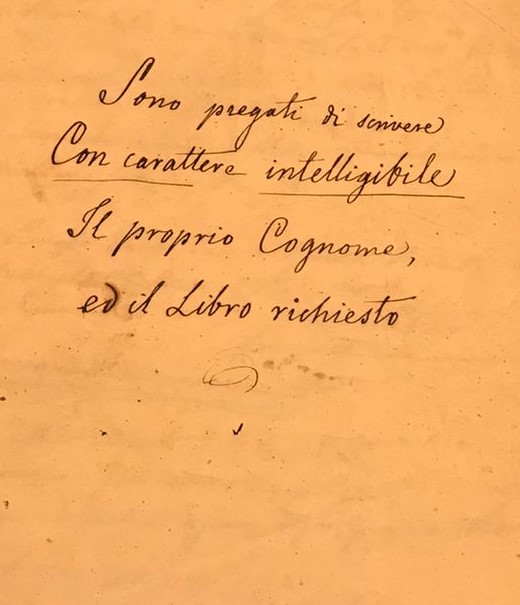

On the front plate of Ms. Cas. 493/1 (1872-1873) is glued to the front plate, and on it a handwritten note informs that ‘The people who go to study in the Biblioteca Casanatense are requested to mark daily in this Register their name and surname, the works they request, and the subject of the same; and, before leaving the Library, to return the books to the Bibliotecarj desk’ (remember that the rules for the proper maintenance of “registers of printed or manuscript works given daily for reading” date back to Royal Decree no. 3464 of 28 October 1885). 3464); another anonymous hand, on a sheet inserted between the verso of paper 1 and the recto of paper 2, also instructs readers to write ‘in intelligible character’ their name and the work requested.

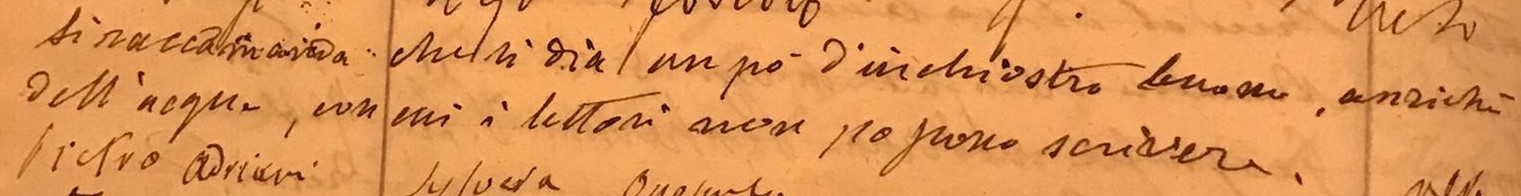

Let us therefore move on from the general ‘instructions for use’ of an instrument made available to readers, to a more marked historical trace, through the following note, placed next to the date 5 November 1873, in Ms. Cas. 493/2 (1873-1875): ‘Day on which possession of the Library was taken’. After the law of 19 June 1873, n. 1402, the Casanatense continued its alternating vicissitudes and Dominican quarrels with the Italian State and shared, until 1885, the fate of the ‘Vittorio Emanuele II’, with which it was a ‘condominium’ (as Vincenzo de Gregorio writes). The disastrous fate of the joint administration of the two libraries, for which neither was able to resolve itself, is highlighted well by another anonymous note, dated 1875, and still in Ms. Cas. 493/2: ‘It is recommended that some good ink be given, instead of water, with which readers cannot write’ (who knows if it is possible to trace some complaint in the nineteenth-century records of the Biblioteca Nazionale in Rome as well).

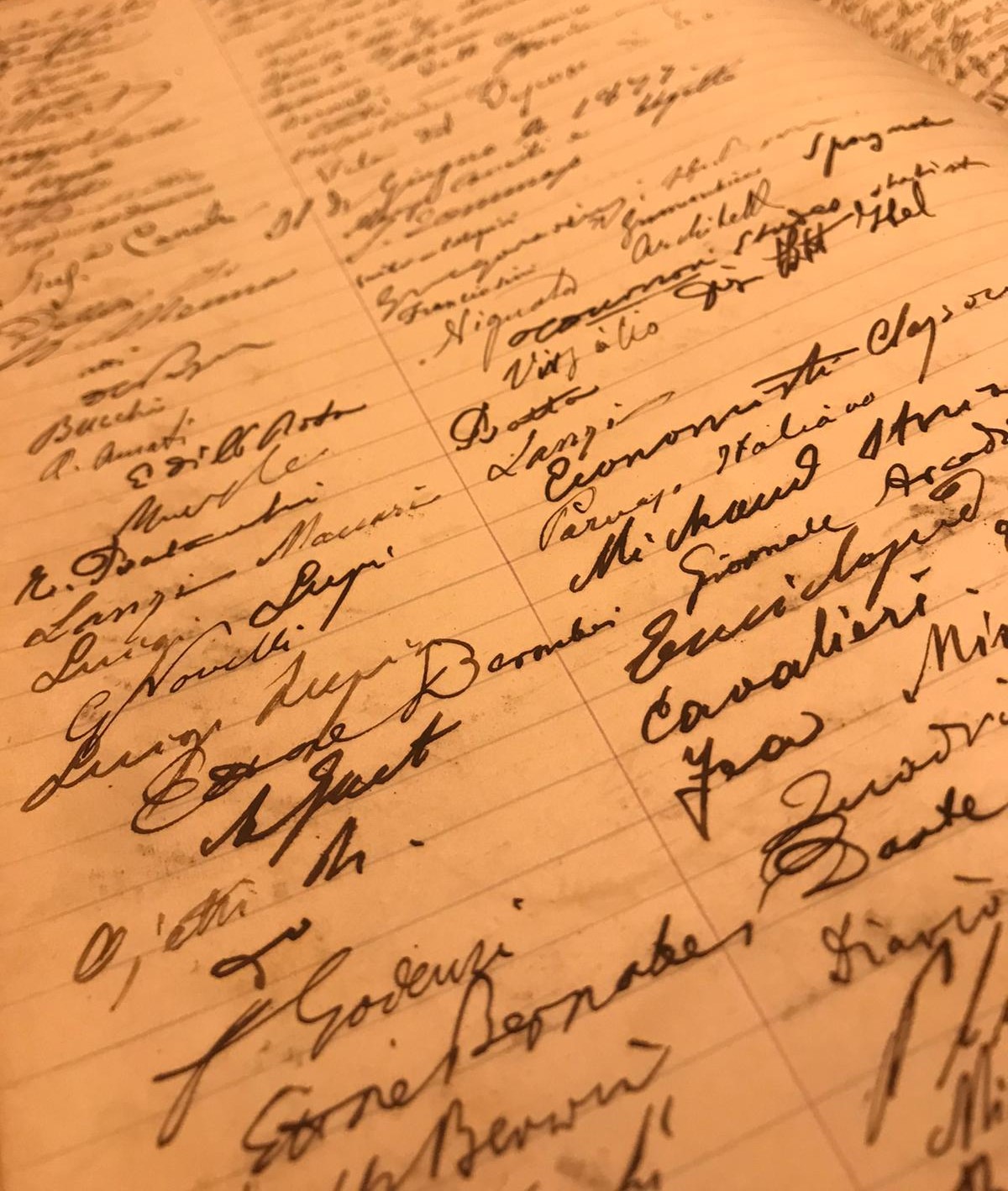

Another historical trace, but this time a silent one, of the crucial and transitional moment in these years can be seen in the absence, for the year 1874 (probably the least defined and most confusing, since it followed the Library’s transfer to the Italian State), of readers’ signatures: the only day noted in Ms. Cas. 493/2 is February 2, 1874 (Ms. Cas. 493/2 resumes about a year later, on March 2, 1875) and the total audience recorded on this day (by a single hand, probably that of the distributor) is 70 readers, while the works requested for reading are 126.

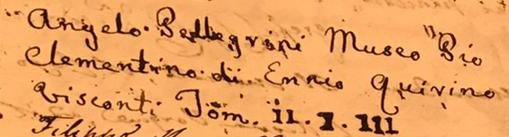

The Casanatense public, between 1872 and 1880 (Ms. Cas. 493/1-8), was always well nourished, because one did not enter the Library just to study, as is well shown by the jokes of one reader: ‘Angelo Pellegrini wrote without taking any books’, ‘Pellegrini Angelo alone intervened’, ‘Pellegrini Angelo nothing’, ‘Pellegrini Angelo nothing taken’.

The signature of Angelo Pellegrini, a member of the Institute of Archaeological Correspondence and chief delegate of the Inspectorate of Antiquities in Rome, is the first we encounter in Ms. Cas. 493/1.

He is a Roman archaeologist and the author of a wealth of erudite, epigraphic and antiquarian publications on Rome. Archaeologists, on the other hand, constitute an important group within the Casanatense: We can trace the famous names of the Italians Giovanni Battista de Rossi (1822-1894), Fabio Gori (1833-1916), Vincenzo Forcella (1869-1884) and Orazio Marucchi (1852-1931); a microgroup of archaeologists from beyond the Alps consists of Victor Schultze (1851-1937), Nikodim Pavlovič Kondakov (1844-1925) and Louis Marie Olivier Duchesne (1843-1922): the latter among the participants of the Collegium cultorum martyrum, also founded on 2 February 1879 by Orazio Marucchi.

The international audience includes: Claude Delaval Cobham (1824-1915), commissioner of the British government in Cyprus; Rudolf Kleinpaul (1845-1918), German philologist and essayist; musicologist Wilhelm Meyer (1845-1917); Ricardo Bellver (1845-1924), Spanish sculptor; Eugène Müntz (1845-1924), French art historian and member of the Ècole française; French composer Paul Puget (1848-1917); New York painter Eugene Benson (1839-1908); Georg Theodor Schreiber (1848-1913), German archaeologist; Georges Dury (1853-1918), French historian and novelist; Spanish writer Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo (1856-1912); Arthur Lincoln Frothingham (1859-1923), American archaeologist; Marcus Jacob Monrad (1816-1897), Norwegian theologian and philosopher; Joseph Hyacinte Albanès (1822-1897), French historian and ecclesiastic;

Magontine historian and librarian Heinrich Heidenheimer (1856-1941); German church historian Karl Benrath (1845-1924); Marie-René de La Blanchère (1853-1896), French epigraphist; French medievalist Paul Durrieu (1855-1925); French writer André de Bellecombe (1822-1892); the Asturian historian, philanthropist and art lover Fortunato de Selgas (1838-1921); Alexandre Brisse (1822-1892), French engineer, famous for completing the draining of Lake Fucino in 1876; the Polish archivist and bibliographer Teodor Wierzbowski (1853-1923); August Schmarsow (1853-1936), German art critic.

Well-known personalities are those of Costantino Corvisieri (1822-1898), a famous investigator of things Roman; Ferdinand Gregorovius (1821-1891), German medievalist and historian; Vittorio Imbriani (1840-1886), storyteller and journalist; Ugo Balzani (1847-1916), compiler of the catalogue of manuscripts of the BVE; Luigi Pigorini (1842-1925), founder of the Museo Preistorico Etnografico; Ernesto Monaci (1844-1918), philologist and one of the founders of the Istituto storico italiano per il Medioevo;

Edmund Stengel (1845-1935), one of the founders, with Monaci, of the Rivista di filologia romanza; Arturo Graf (1848-1913), professor of Neo-Latin and Italian literature; Antonio Pozzo and Celestino Schiaparelli (1841-1919), the former a disciple of Luigi Calligaris, professor of Arabic in Turin, the latter a celebrated Arabist. Among the librarians, we can find the signatures of Salomone Morpurgo (1860-1942), Enrico Narducci (1832-1893), Bartolomeo Podestà (1820-1910), Domenico Gnoli (1838-1915), Valentino Cerruti (1850-1909) and Ettore Novelli (1822-1900).

There is of course no shortage of religious: the Waldensian Oscar Cocorda (1833-1916); Franz Steffens (1853-1930), palaeographer (at the time, a theology student in Rome); Pietro Arbanasisch (1841-1905), Garibaldine and evangelist; Gaetano Lironi (1817-1889), bishop of Assisi; Gaetano de Lai (1853-1928), cardinal and bishop; Odon Delarc (1839-1898), French priest and historian; Alessio di Sarachaga (1840-1918), founder of the Paray le Monial ecauristic museum in Burgundy-France; Luigi Tripepi (1836-1906), prefect of the Vatican Archives, consulter of the S. Uffizio and Cardinal Calabrese; Nicola Averardi (1823-1924), archbishop and apostolic nuncio to France; Generoso Calenzio (1836-1915), librarian of the Vallicelliana; Victor Jouët (1839-1912), from Marseilles and founder of the Church of the Sacred Heart of the Suffrage, very close to Castel Sant’Angelo, and of the museum of the fire ‘imprints’ left by the souls in Purgatory on various objects, which are still on display in the Church; Giuseppe Lais (1845-1921), assistant to Angelo Secchi at the Observatory of the Roman College.

Among the politicians and patriots were: Oscar de Poli (1838-1908), French man of letters and prefect, in 1860 enlisted in the army corps of the Papal Zouaves; Adolf Rhomberg (1851-1921), Austrian businessman and governor; Achille Sacchi (1827-1890), doctor and patriot from Mantua; Giuseppe Salemi Oddo (1826-1913), deputy and elected representative in the Termini Imerese constituency of the Chamber of Deputies; Filippo Spatafora (1830-1913), Mazzinian and anti-monarchist, president of the Rome Action Committee from 1862 to 1867 and later clerk of the Rome City Council; Tommaso Tittoni (1855-1931), Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1903 to 1905 and then of the Interior, diplomat and, for a short time, President of the Council of Ministers; Oreste Tommasini (1844-1919), historian, liberal and progressive, Senator of the Kingdom of Italy in 1905.

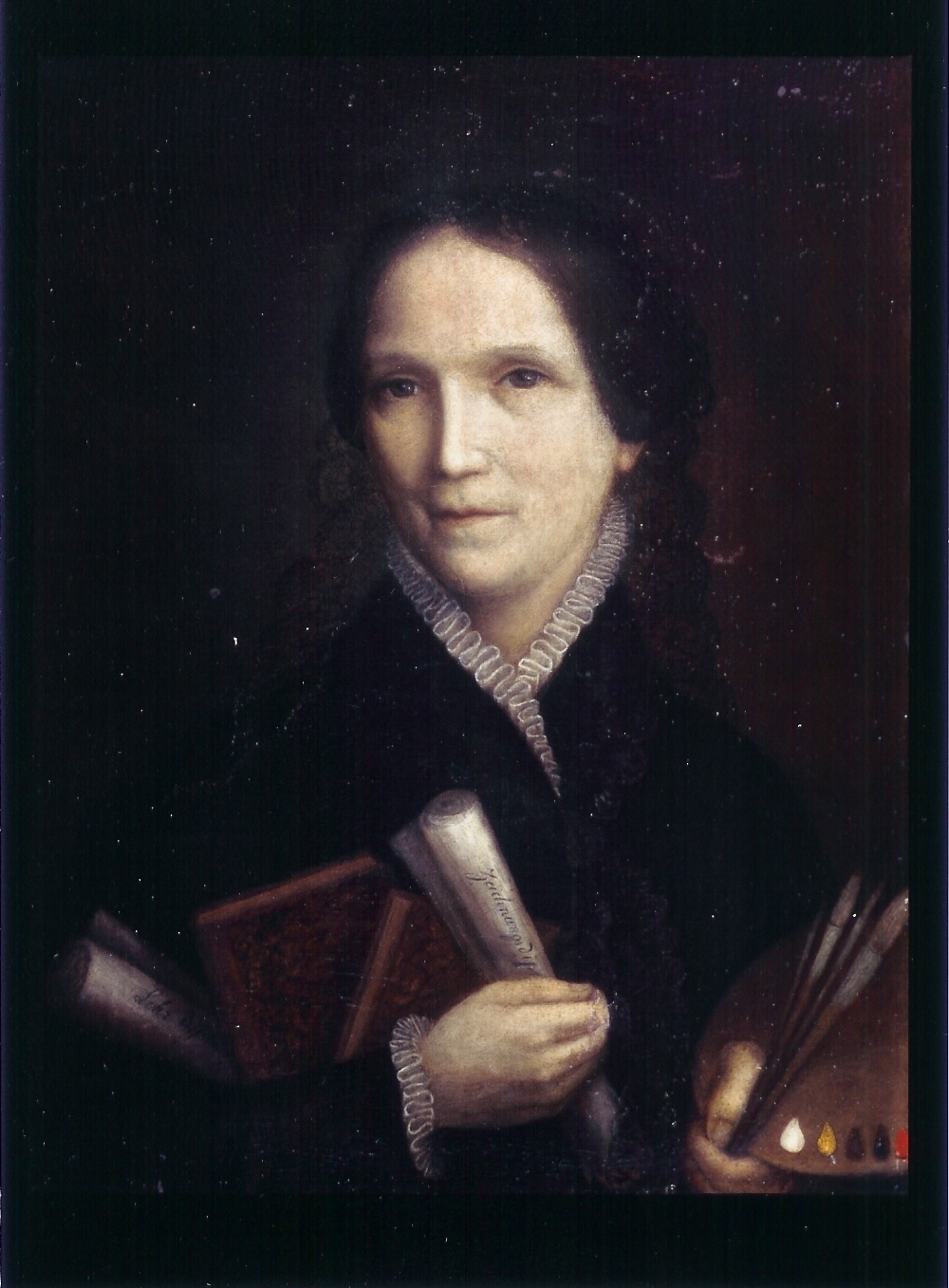

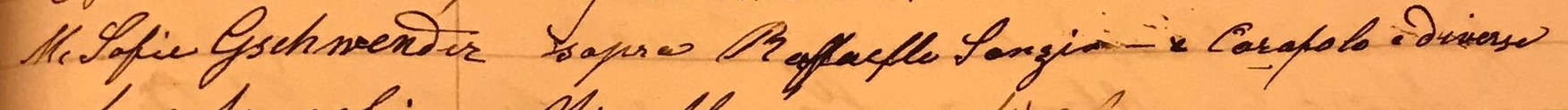

In 1877 we find the name of a woman in the register of readers: M. Sofia Gschwender (1816-1897), originally from Oberstdorf, the daughter of a shopkeeper. In 1841 she went to Italy for the first time, in 1844 she was in Augsburg, where she succeeded in studying and became a teacher of drawing and languages; in 1849 she took her vows but soon moved to France, to Pau: here she was an educator, artist and art dealer. She returned to her hometown between 1874 and 1875 where she had ‘Café Knaus’ built: in 1888 she opened a picture gallery with paintings from her collection, with two canvases attributed by Gschwender to Rffaello. And perhaps in 1877 he was in Rome to do research on the famous Renaissance painter from Urbino: at the Casanatense, he consulted antique prints on Raffaello Sanzio.

The biographical profile of the second woman, and reader, at the Casanatense was decidedly different: Clelia Bertini (1862-1915), a Roman writer and poetess, who graduated in Literature and taught in Naples at the ‘Eleonora Fonseca Pimentel’ School, and in 1896 was teacher of the preparatory course at the Royal Normal School for Women ‘Giannina Milli’, at the Arco del Monte (since 1883 the School has been named after Vittoria Colonna).

In conclusion, we can say how the Casanatense Library is traversed, from 1872 to 1880, by a large section of the public (Roman, Italian and international) who use its rich heritage to study and read; and then there are those who, like Angelo Pellegrini, intervene only ‘to clean up some of his writings’.

Let us therefore end on a roundabout note, with our first author quoted and encountered in the readers’ records, by recalling that the role of libraries is not only to collect and preserve books and documents, but above all to enable a society to investigate itself, to do research, to inform itself and to browse beyond its collections.