In each presentation of autographs of more or less famous people, the aim is to add a small piece of history to the knowledge of their lives, to reconstruct perhaps minor episodes of their private life or lesser-known public aspects. In the shadow of works to which memory is entrusted, they wove, like any other mortal, human relationships, had practical concerns, maintained formal relations: their personality was reflected in a thousand different mirrors. The content of the writings, the occasion and the context that inspired them, are a first evident mirror that illuminates their daily life; writing as a material support for thought is a second in which the innate qualities of character are reflected and an ideal hierarchy of values is represented. Graphology as a technique for interpreting writing, equipped with its own lexicon, principles and classification, was born at the end of the 19th century with Michon, the first who was able to crown a flurry of often superficial attempts with his Système de graphologie of 1875.

In each presentation of autographs of more or less famous people, the aim is to add a small piece of history to the knowledge of their lives, to reconstruct perhaps minor episodes of their private life or lesser-known public aspects. In the shadow of works to which memory is entrusted, they wove, like any other mortal, human relationships, had practical concerns, maintained formal relations: their personality was reflected in a thousand different mirrors. The content of the writings, the occasion and the context that inspired them, are a first evident mirror that illuminates their daily life; writing as a material support for thought is a second in which the innate qualities of character are reflected and an ideal hierarchy of values is represented. Graphology as a technique for interpreting writing, equipped with its own lexicon, principles and classification, was born at the end of the 19th century with Michon, the first who was able to crown a flurry of often superficial attempts with his Système de graphologie of 1875.  Michon based himself on principles derived at the same time from Descartes and the sensualism of Condillac; the belief in a one-to-one correspondence between physiological and psychological movements allowed him to consider the canons of graphology valid for writings of all times and places, and to establish it as a science. From then on, while continuing in the path he had traced, graphology has changed, acquiring a new awareness of its potential and its limits. Crépieux-Jamin questioned the existence of a fixed relationship between graphic sign and psychological sign, highlighting the importance of the starting calligraphic model and the graphic context, Klages and Pulver underlined its nature as a flexible instrument, also linked to the interpreter who does not so much decode as explore the symbolic dimension of writing, leading graphology to share the fascination and risks of a hermeneutics of personality.

Michon based himself on principles derived at the same time from Descartes and the sensualism of Condillac; the belief in a one-to-one correspondence between physiological and psychological movements allowed him to consider the canons of graphology valid for writings of all times and places, and to establish it as a science. From then on, while continuing in the path he had traced, graphology has changed, acquiring a new awareness of its potential and its limits. Crépieux-Jamin questioned the existence of a fixed relationship between graphic sign and psychological sign, highlighting the importance of the starting calligraphic model and the graphic context, Klages and Pulver underlined its nature as a flexible instrument, also linked to the interpreter who does not so much decode as explore the symbolic dimension of writing, leading graphology to share the fascination and risks of a hermeneutics of personality.

The graphological portrait therefore admits to being a point of view, as rigorous as possible, but partial, a mirror that reflects the personality, but an unfaithful mirror; after all, isn’t this perhaps a necessary limit for any investigation into human nature?

In addition to the intimate relationship that is established between the writer and the graphologist, and involves both, a third element comes to the fore when analyzing the writings of famous people. And the risk of superimposing on the analysis what is known about them starting from their works. An error that has not spared eminent graphologists: among the first, Moretti who had examined a manuscript by Giacomo Leopardi, finding the typical traits of Leopardi’s poetics. Unfortunately, the manuscript was not by the famous poet, but by his nephew of the same name!

Have we escaped this temptation? Was it possible or desirable to escape it? In other words, is it better to ignore or to know whose writing we are analyzing?  It is now common opinion among graphologists to have basic information about the author of the writing that includes at least sex and social and professional status, and, according to some, all the information that can be collected. Writing is then considered as one of the traces that man leaves of his path, perhaps more authentic and less perishable than others, but not even it self-sufficient. Thus, by giving up the claim of providing the only “true” access to personality, graphological analysis can benefit greatly from comparing itself with the philosophy of the writer, and with his personal history: for this we have sometimes used anecdotes that compared to biographies, usually animated by laudatory intentions, are less flattering and often contain in a single sentence, or gesture, an entire symbolic universe.

It is now common opinion among graphologists to have basic information about the author of the writing that includes at least sex and social and professional status, and, according to some, all the information that can be collected. Writing is then considered as one of the traces that man leaves of his path, perhaps more authentic and less perishable than others, but not even it self-sufficient. Thus, by giving up the claim of providing the only “true” access to personality, graphological analysis can benefit greatly from comparing itself with the philosophy of the writer, and with his personal history: for this we have sometimes used anecdotes that compared to biographies, usually animated by laudatory intentions, are less flattering and often contain in a single sentence, or gesture, an entire symbolic universe.

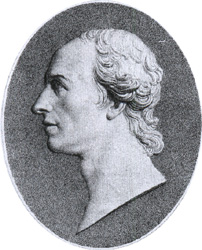

Antonio Canova

Antonio Canova

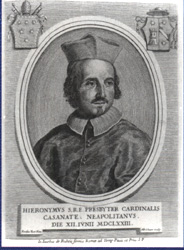

Presenting these Casanatensi autographs also from a graphological point of view can therefore reserve, as we hope, some surprises, but it is not spying on famous people “from the back stairs”, it is not discovering an “inside” instead of an “outside”, a private person that no one knows compared to what is in the public domain. Writing, especially when it comes to letters addressed to an addressee, also makes its entrance through the main door, it is controlled, announced, and every attempt to analyze it must take into account, sometimes to contrast them, more often to nuance or confirm them, also other readings. Because by writing we reveal ourselves, but we also hide ourselves and, in autographs, as in any other human product, being and appearance, character and ideals are found intertwined in ambiguous, sometimes inextricable knots.