by Margherita Palumbo

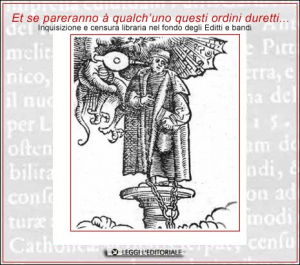

Inquisition and book censorship in the collection of Edicts and Proclamations

Inquisition and book censorship in the collection of Edicts and Proclamations

The opening to scholars in 1998 of the Historical Archives of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith has contributed to a profound renewal of studies on the history of the Inquisition, and at the same time there has been a considerable growth in interest on the part of the scientific community in the decrees and edicts issued, in their jurisdictional sphere, by the Congregation of the Holy Roman Inquisition – also known as the Holy Office – and that of the Index. In this context, the Casanatense Library has long been recognized as one of the privileged research centers, thanks in particular to the very rich collection of Papal Edicts and Proclamations preserved by the Institute, a collection that as a whole includes, in a period of time that goes from the beginning of the sixteenth century to 1870, over 70,000 documents bound, in chronological succession, in large-format volumes, and of which approximately 1,500 are those that concern matters of inquisitorial competence. First of all, mention must be made of the bulls, constitutions and other provisions issued by the pontiffs themselves on doctrinal questions, on matters of dogma and on crimes concerning, even in a broad sense, faith.

Announcement and provision… about books. Rome, 1591

Announcement and provision… about books. Rome, 1591

This first category includes documents such as the bull Cum quorundam hominum pravitas issued in 1555 by Paul IV against the anti-Trinitarians. Per.est. 18/1, n. 96 ), or the Coeli et terra of 1586, with which Sixtus V condemned judicial astrology and other forms of cultured magic (Per. est. 18/2 n. 131 ), as well as the founding acts of the Congregations of the Inquisition and the Index themselves and those relating to the definition, over the centuries, of their competences, activities and powers, starting from the bull Licet ab initio with which Paul III in 1542 outlined the structure and powers of the Holy Office.

As regards the edicts themselves, particularly numerous are – within the Casanatense collection – the decrees issued by the Congregation of the Inquisition, with a variety that reflects the very breadth of the powers of the central body established by Pope Farnese in order to fight and legally defeat, in addition to heretical depravity, apostasy from Judaism and Islam, blasphemy, simulated sanctity, bad administration of the sacrament of penance, and in particular solicitation in confession, and other crimes against faith and morals.

Announcement and provision… about books. Rome, 1591

Announcement and provision… about books. Rome, 1591

Another significant group of provisions traceable among the Edicts and proclamations concerns the censorship and control of the press and book trade, acts which could also be issued by the Pope himself, as in the case, in 1592, of the Constitutio contra impia scripta et libros Hebraeorum by Clement VIII (Per.est. 18/3, n. 17 ) or the later damnatio of Clement XI which struck, in 1708, the writings of the Jansenist Quesnel (Per.est. 18/22, n. 88 ) and then confirmed in 1713 by Unigenitus Dei filius (Per.est. 18/23, n. 534 ).

Più numerosi sono però i documenti la cui emanazione rientra sia nelle attribuzioni della Congregazione del S. Uffizio e di quella, di più tarda istituzione, dell’Indice, sia nella sfera di autorità del Maestro del Sacro Palazzo, membro ex officio e portavoce di entrambe le Congregazioni, delle cui condanne dava pubblica notizia attraverso editti a stampa di proibizione.

Index of prohibited books. Rome, 1603

Index of prohibited books. Rome, 1603

This category includes the decrees that made public – thanks to posting in designated places – famous sentences, such as the edict of 7 August 1603 by the Master of the Sacred Palace Giovanni Maria Guanzelli from Brisighella, later reiterated under the pontificate of Paul V Borghese, which placed the entire work of Giordano Bruno and Tommaso Campanella on the Index (Per.est. 18/3, nn. 301 bis-ter ); the decree of 1616 concerning Copernicanism (Per.est. 18/4, n. 417 ), or the edict of 1634 which lists, among the titles to be prohibited because they are contrary to Catholic orthodoxy, Galileo’s Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems (Per.est. 18/6, n. 53 ), then moving on to the condemnation of the books of Miguel de Molinos (Per.est. 18/15, n. 344 ), guilty of having spread the poison of quietism, up to the prohibitions that in the eighteenth century inexorably struck the supporters of the libertas philosophandi, or even erudite newspapers of wide European circulation such as the Acta eruditorum of Leipzig. If such prohibition edicts are often the outcome of highly resounding trials, less known – but no less effective – are the provisions that acted against popular superstition through the condemnation of widespread Operette, Historie, Orationi, devotional writings, litanies, apocryphal hagiographic legends, collections of false indulgences, such as The Seven Joys of the Madonna, prohibited throughout the Papal State in the early seventeenth century (see for example Per.est. 18/4, n. 376bis ), while a similar prohibition decree struck in 1677 the very widespread Devotioni in honor of St. Anna, pamphlets of a few pages which support the immaculate conception of the saint.

Coat of arms of Pope Paul IV

Coat of arms of Pope Paul IV

Most of the prohibitions contained in the edicts intended for posting ended up being included in the Indexes of Prohibited Books periodically printed with the authorization of the Pope himself, and of which the Casanatense possesses an almost uninterrupted series, from the Index librorum prohibitorum printed between 1558 and 1559, at the request of Paul IV Carafa, to the last edition published in 1948 during the pontificate of Pius XII.

A further and valuable addition to the documentation preserved in the Editti e bani collection – and only exemplified here – is then offered by the numerous inquisitorial manuals and repertoires owned by the library, such as the Directorium Inquisitorum by Nicolás Eymerich, the Tractatus de haeresi by Prospero Farinacci and the Sacro arsenale by Eliseo Masini, together with many other treatises for the use of the Inquisitors, including the very rare Scriniolum Sanctae Inquisitionis Astensis, published in Asti in 1610, a precious source not only for the reconstruction of the history of book censorship in Italy, but also for a better understanding of the complex relationship between central authority and peripheral branches of the inquisitorial tribunals ( P.I.43 CC ).

Of great interest, finally, within the volumes of the Edicts and Proclamations, are the provisions published, up until the end of the eighteenth century, by the Master of the Sacred Palace with the aim of regulating and controlling, down to the smallest details, all the phases of book production and trade, prescribing strict rules for Booksellers, Printers, Engravers, Book Engravers, Customs Officers, Couriers, Postmen, Porters, while a specific article is addressed to the Jews, because «no Jew or second-hand dealer can buy or sell books of any kind without having had an express written license» (Per.est. 18/2, n. 20bis ).

The penalties for violating these provisions are severe and can involve, in addition to the seizure of books, also heavy fines and corporal punishment. The control activity obviously does not ignore private libraries, “both for the living and for the dead”. In the event of the death of the owner, the heirs were in fact required to deliver a copy of the inventories to the Master of the Sacred Palace, in order to verify the presence of suspicious texts in the collection, while an example of how the censorship machine could strike, in addition to authors and owners, also printers and booksellers is the excommunication in 1606 by Paul V of the Venetian printer Roberto Meietti, already guilty in 1599 of having clandestinely imported from Germany a volume of the prohibited Centuriae Magdeburgenses by Flacius Illyricus. In the Instruction and warnings for those who want to print books in Rome of 1607, the aforementioned Guanzelli reiterated – as many other Masters of the Sacred Palace would later do – the provisions regarding printing, concluding as follows: «And if these orders seem harsh to anyone, let them stop printing, since at the same time they will be out of expense, we out of trouble, and both out of danger, and great harm will be done to the Republic, since there is as much of a quantity of books as anyone can see» ( Per.est. 18/4, n. 124bis ).

Coat of arms of Pope Urban VIII

Coat of arms of Pope Urban VIII

Bibliography

![]() Registers of proclamations, edicts, notifications and various provisions relating to the city of Rome and the Papal State, Rome, Cuggiani, 1920-1958.

Registers of proclamations, edicts, notifications and various provisions relating to the city of Rome and the Papal State, Rome, Cuggiani, 1920-1958.![]() Index des livres interdits. Directeur J. M. De Bujanda, Sherbrooke, Centre d’Études de la Renaissance, Éditions de l’Université de Sherbrooke (Librairie Droz), 1985-2002.

Index des livres interdits. Directeur J. M. De Bujanda, Sherbrooke, Centre d’Études de la Renaissance, Éditions de l’Université de Sherbrooke (Librairie Droz), 1985-2002. ![]() Inquisition and Index in the XVI-XVIII centuries. Theological controversies from the Casanatensi collections, Vigevano, Diakronia 1988.

Inquisition and Index in the XVI-XVIII centuries. Theological controversies from the Casanatensi collections, Vigevano, Diakronia 1988. ![]() E. Canone, The edict prohibiting the works of Bruno and Campanella, «Bruniana Campanelliana», I (1995), pp. 43-61.

E. Canone, The edict prohibiting the works of Bruno and Campanella, «Bruniana Campanelliana», I (1995), pp. 43-61.![]() Giordano Bruno, 1548-1600. Historical documentary exhibition (Rome, Casanatense Library, 7 June-30 September 2000), Florence, Olschki, 2000, in part. pp.201-209.

Giordano Bruno, 1548-1600. Historical documentary exhibition (Rome, Casanatense Library, 7 June-30 September 2000), Florence, Olschki, 2000, in part. pp.201-209. ![]() J. M. De Bujanda – E. Canone, The edict prohibiting the works of Bruno and Campanella. A bibliographical analysis, «Bruniana Campanelliana», VIII (2002), pp. 451-479.

J. M. De Bujanda – E. Canone, The edict prohibiting the works of Bruno and Campanella. A bibliographical analysis, «Bruniana Campanelliana», VIII (2002), pp. 451-479. ![]() M.-P. Lerner, Copernic suspendu et corrigé: sur deux décrets de la Congrégation Romaine de l’Index (1616-1620), «Galileiana», I (2004), pp. 21-89

M.-P. Lerner, Copernic suspendu et corrigé: sur deux décrets de la Congrégation Romaine de l’Index (1616-1620), «Galileiana», I (2004), pp. 21-89

Inquisition and book censorship in the collection of Edicts and Proclamations

Inquisition and book censorship in the collection of Edicts and Proclamations