by Andrea Cappa

The Giulio Cesare casanatense (Ms. 453)

The Giulio Cesare casanatense (Ms. 453)

The attack is one of those that are not forgotten, a memorable incipit, that anyone who has studied a little Latin rediscovers sedimented in the depths of memory, sometimes almost unconsciously, words now separated from a past of studies, beyond grammar and literature, a distant echo that is a common heritage, Gallia est omnis divisa …

And after this brief beginning, the mind suddenly opens up to endless fir forests, humid valleys and foggy mountains, epic battles, ferocious barbarian populations, the Celts, or Gauls, the Germans, the Britons, the courageous composure of the Roman phalanxes, the heroism of the tenth legion, and Lutetia and Vercingetorix and then him, general, politician and historian, perhaps the most beloved writer of antiquity, for his spare and essential style, for those faithful and precise narrations, for that world of Nordic mists, bloody clashes and military strategies that still fascinate us today. Julius Caesar, the classic par excellence, supporter and narrator of the triumphs of Rome, who has never read him?

Manuscript 453 of the Casanatense Library is one of the most precious of the codices containing Caesar’s text, a splendid luxury humanistic volume dating back to the second half of the 15th century, more precisely to around 1470, and produced in Rome in the artistic environment that gravitated around the papal court and the nascent Vatican Library.

Manuscript 453 of the Casanatense Library is one of the most precious of the codices containing Caesar’s text, a splendid luxury humanistic volume dating back to the second half of the 15th century, more precisely to around 1470, and produced in Rome in the artistic environment that gravitated around the papal court and the nascent Vatican Library.

Rome in those years, under the pontificates of Paul II and then Sixtus IV, was a true “workshop” of Humanism; Pomponio Leto, founder of the Roman Academy, held his lectures there, classical studies were in full swing, the passion for antiquity and archaeological research provided continuous inspiration to painters and miniaturists, who could convey the suggestions of antiquity in their works.

The appearance of classicising elements was a relatively new fact, essentially linked to the work of Andrea Mantegna in his Paduan period, and in the Veneto in general, towards the middle of the century, when works rich in quotations from the ancient world such as the frescoes in the Ovetari Chapel in Padua and the altarpiece of San Zeno in Verona had given rise to talk of a “new painting”, which then also influenced the so-called “ancient” miniature.

The Venetian artistic environment, in the wake of Mantegna and Francesco Squarcione, around whose workshop many people trained, promoted a true revolution in taste, which imposed the classicizing style, supplanting decorative modules that were sometimes still of a fourteenth-century style and the Florentine fashion of the “bianchi girari”.

Under Pope Paul II (1464-1471), the Venetian Pietro Barbo, there was a real migration of Venetian artists to Rome, and among these the Paduans Bartolomeo Sanvito and Gaspare, respectively copyist and illuminator of the manuscript in question; to them we owe in Rome a splendid production of “ancient” illuminated codices, mostly preserved in the Vatican Apostolic Library.

Although lacking a colophon or any clarifying note, Giulio Cesare has been attributed to this environment since the 1950s, of which however little was known, only later, thanks to Tammaro De Marinis, identifying the unmistakable hand of Bartolomeo Sanvito in the very elegant cursive humanism. Today, over 100 codices can be traced back to his activity as a calligrapher, in which he appears as a copyist, as a rubricator, even as an illuminator in some cases, over a period of over 50 years, outlining a production that is very rich from a qualitative and quantitative point of view. Many maintain that his handwriting inspired Aldo Manuzio to create the “italic” character.

The attribution of the miniature is more complex: according to some it can be attributed to the copyist himself, according to others to Gaspare, even if a comparative stylistic analysis leads to opting almost definitively for the second theory, by virtue of the extremely high artistic quality.

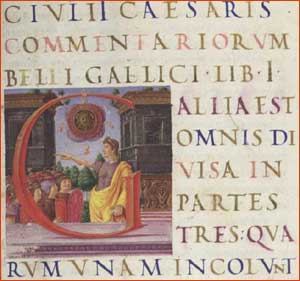

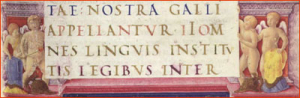

The decorative apparatus, in fact, sober but at the same time extremely refined, is composed of a purple frontispiece, an architectural frontispiece, and 14 large Litterae Mantinianae placed at the beginning of each individual book of the Commentarii, with a “perfect symbiosis of text and ornamentation”, so much so as to represent “a true paradigm of humanistic meditation on the forms and spirit of Romanity”.

The decorative apparatus, in fact, sober but at the same time extremely refined, is composed of a purple frontispiece, an architectural frontispiece, and 14 large Litterae Mantinianae placed at the beginning of each individual book of the Commentarii, with a “perfect symbiosis of text and ornamentation”, so much so as to represent “a true paradigm of humanistic meditation on the forms and spirit of Romanity”.

The purple frontispiece, a learned quotation from the ancient, is a typical example of the way in which Sanvito uses dyed parchments, limiting himself to the insertion of even a single sheet: on a purple background, the triumph of Caesar is drawn in sanguine and black ink, with golden highlights, with a parade of chariots that passes through a large arch and follows the procession of soldiers and prisoners. Between the latter and the horses, some victories appear, while in the background an almost unreal Rome appears, with an appearance perhaps more Renaissance than ancient. The triumphal images are borrowed from the Arch of Titus and that of Constantine. The drawing suggests an idea of incompleteness, in the lack of ink on the left half, and may lead one to think that the decoration was not completed, a doubt that may be confirmed by some spaces that remained blank in the lower part of the frontispiece.

Here an imposing classical aedicule rests on a grassy insula and serves as a frame for the text: at the base of the aedicule, a blue plinth reproduces, with the technique of golden highlights on a monochrome background, a battle scene that recalls the bas-reliefs of triumphal columns.

On both sides of the plinth, a double pair of golden winged lions, also on a blue background, supports a white space intended to house the patron’s coat of arms, which was never painted. Also incomplete, and left white, is a façade of the base, right next to the pair of lions on the right. Above them, on the sides of the text, imagined on a perfectly rectangular sheet of paper, appears a double pair of winged cherubs on a deep red background, in the middle of helmets and armor.

In the still uppermost section of the aedicule, on a green background, on both sides, a fake bas-relief of weapons, shields, helmets, spolia opima, with an unfortunately evident abrasion in the left area. Immediately above, still on the sides of the sheet, a very colorful and imaginative portico, where the pillars, on a purple background, have a base and capital in gold. The culminating part of the aedicule sets a small frieze, which always unfolds on the sides of the central sheet, in which a double pair of winged lions is depicted, of small size, divided by a palmette.

In the still uppermost section of the aedicule, on a green background, on both sides, a fake bas-relief of weapons, shields, helmets, spolia opima, with an unfortunately evident abrasion in the left area. Immediately above, still on the sides of the sheet, a very colorful and imaginative portico, where the pillars, on a purple background, have a base and capital in gold. The culminating part of the aedicule sets a small frieze, which always unfolds on the sides of the central sheet, in which a double pair of winged lions is depicted, of small size, divided by a palmette.

Above the aedicule, finally, putti and fauns wrapped in yellow and blue draperies play, while a final semi-circular architectural element emerges from behind the text with images of dolphins with intertwined tails. In the foreground, standing out on the page like an epigraph, the text, with the indications of author and title, and with the incipit of the Commentarii de bello Gallico.

It consists of 17 lines of writing written in splendid epigraphic capitals, and in each of them a letter in gold leaf alternates with another of a different color, one different for each line, in the order of blue, pink, pale green, purple. The chiaroscuro effect, the correct arrangement of solids and fillets, the use of elegant ornamental serifs reveals a profound assimilation of the lesson of Leon Battista Alberti and of the circle of humanists engaged in the study of ancient epigraphy.

From the fourth line to the eighth, half of the writing surface is occupied by the large amaranth-colored Mantiniana “G,” on a quadrangular plaque, depicting Caesar haranguing the soldiers, with a background of two facing monumental buildings; a two-tone wisteria-bronze quadrilobed clipeus hangs from the letter itself, to which it is attached by a sort of ribbon, and sets a head of Medusa. Various chromatic tones, especially in the soldiers’ clothes and shields, in warm tones, and a very young Julius Caesar depicted in a yellow cloak. The three-dimensional character of the letter is strong, appearing to protrude from the background thanks to the illusion of perspective, made more powerful by the chiaroscuro effect obtained through the gold highlights.

The great Mantiniana of the incipit is followed by another fourteen, which, accompanied by some lines of capital letters written in colored ink and gold, represent the only further ornamental element of the manuscript. In fact, despite the splendor of the decorations, the true protagonist is the text of the transmitted work, since, according to a tradition that has its roots in the medieval world, the culture of images could not be allowed to prevail over written culture.

ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

ESSENTIAL BIBLIOGRAPHY![]() G. Baldissin Molli, G. Canova Mariani, F. Toniolo (edited by), Painted Words: Miniatures in Padua from the Middle Ages to the Eighteenth Century, Modena, Panini, 1999.

G. Baldissin Molli, G. Canova Mariani, F. Toniolo (edited by), Painted Words: Miniatures in Padua from the Middle Ages to the Eighteenth Century, Modena, Panini, 1999.![]() A. Cappa, Humanism, antiquarian passion and book production between Padua and Rome in the mid-1400s: the Casanatense Giulio Cesare, in “Schol(i)a”, 2 (2004), pp. 54-105

A. Cappa, Humanism, antiquarian passion and book production between Padua and Rome in the mid-1400s: the Casanatense Giulio Cesare, in “Schol(i)a”, 2 (2004), pp. 54-105![]() S. De Kunert, An unknown Paduan and his Memorial from the early years of the sixteenth century (1505-1511) with notes on two illuminated manuscripts, in “Bollettino del Museo Civico di Padova”, 10 (1907), pp. 1-16 and 74-63.

S. De Kunert, An unknown Paduan and his Memorial from the early years of the sixteenth century (1505-1511) with notes on two illuminated manuscripts, in “Bollettino del Museo Civico di Padova”, 10 (1907), pp. 1-16 and 74-63.![]() T. De Marinis, Note for Bartolomeo Sanvito, a fifteenth-century calligrapher, in Mélanges Eugène Tisserant, IV, (Studies and texts, 234), Vatican City, 1964, pp. 185-189.

T. De Marinis, Note for Bartolomeo Sanvito, a fifteenth-century calligrapher, in Mélanges Eugène Tisserant, IV, (Studies and texts, 234), Vatican City, 1964, pp. 185-189.![]() A. De Nicolò Salmazo, The renewal of the book in Padua in the age of Humanism, in “Padova e il suo territorio”, 14 (1999), pp. 36-42.

A. De Nicolò Salmazo, The renewal of the book in Padua in the age of Humanism, in “Padova e il suo territorio”, 14 (1999), pp. 36-42.![]() S. Maddalo, “Quasi praeclarissima supellectile”. Papal court and illuminated books in early Renaissance Rome, in “Studi Romani”, 42 (1994), pp. 16-32.

S. Maddalo, “Quasi praeclarissima supellectile”. Papal court and illuminated books in early Renaissance Rome, in “Studi Romani”, 42 (1994), pp. 16-32. ![]() G. Mariani Canova, Purple in Renaissance Manuscripts and the Activity of Bartolomeo Sanvito, in O. Longo (ed.), Purple. Reality and Imagination of a Symbolic Color. Proceedings of the Study Conference (Venice 24 and 25 October 1996), Venice, Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere e Arti, 1998, pp. 339-371.

G. Mariani Canova, Purple in Renaissance Manuscripts and the Activity of Bartolomeo Sanvito, in O. Longo (ed.), Purple. Reality and Imagination of a Symbolic Color. Proceedings of the Study Conference (Venice 24 and 25 October 1996), Venice, Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere e Arti, 1998, pp. 339-371. ![]() A. Petrucci (ed.), Books, Writing and the Public in the Renaissance. Historical and Critical Guide, Bari, Laterza, 1979.

A. Petrucci (ed.), Books, Writing and the Public in the Renaissance. Historical and Critical Guide, Bari, Laterza, 1979. ![]() J. Ruysschaert, The copyist Bartolomeo Sanvito, a Paduan miniaturist in Rome from 1469 to 1501, in “Archive of the Roman Society of National History”, 109 (1986), pp. 37-48.

J. Ruysschaert, The copyist Bartolomeo Sanvito, a Paduan miniaturist in Rome from 1469 to 1501, in “Archive of the Roman Society of National History”, 109 (1986), pp. 37-48.![]() Seeing the Classics: Book Illustration of Ancient Texts from the Roman Age to the Late Middle Ages, Rome, Fratelli Palombi, 1996.

Seeing the Classics: Book Illustration of Ancient Texts from the Roman Age to the Late Middle Ages, Rome, Fratelli Palombi, 1996.

The Giulio Cesare casanatense (Ms. 453)

The Giulio Cesare casanatense (Ms. 453)