The Hortus Romanus by Liberato Sabbati (v. II of Ms. 4460)

The Hortus Romanus by Liberato Sabbati (v. II of Ms. 4460)

The publishing project proposes the printing of the second volume of the Hortus romanus, which was the protagonist of a very painful episode for the Casanatense, which occurred on June 16, 2004. During its exhibition at the Vittoriano, on the occasion of the exhibition “The Roots of the Nation”, the volume – which had been lent – was maliciously stolen, thus impoverishing not only the entire manuscript heritage of the Library, but also invalidating the completeness of the valuable herbarium. Fortunately, the five volumes, which originally constituted the work, had been subjected to a digitalization campaign for which it was deemed possible to somewhat mitigate the damage, although incalculable for the Library, for the heritage of the State and therefore for all citizens, with the reproduction of the illustrations that make up the second volume of the series.

The editorial text is an excerpt from

Hortus Romanus by Liberato Sabbati vol. II (Ms. 4460) edited by Angela Adriana Cavarra and Isabella Ceccopieri. Rome, De Luca editori d’arte c2009

The Ms. 4460: membra disiecta of the Hortus Romanus by Liberato Sabbati

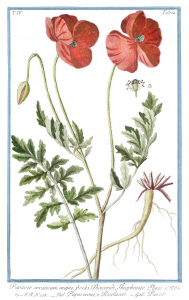

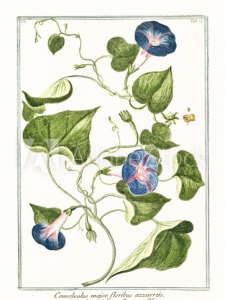

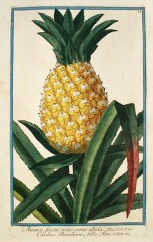

The volume that was preserved in the Casanatense manuscript collection with shelfmark Ms. 4460, constituted the second volume of Sabbati’s Hortus Romanus. The original work, created in 1770, included five manuscript volumes, illustrated by drawings made by Cesare Ubertini, a very close collaborator of Sabbati, who took care of the pictorial layout certainly ad vivum. It is a hortus pictus that belongs to the period of the author’s full maturity, still the first custodian of the Roman botanical garden. His intent was to document the plants preserved there in the herbarium, classifying them according to the system of Joseph Pitton de Tournefort, considered the father of descriptive botany. The Tournefortian method, in fact, identified the plants by dividing them into 22 classes, divided in turn into genera according to the characteristics of the corolla. The taxonomic criteria, no longer aimed at the pharmacological aspects of plants, had by now become the true inspirations of the dry gardens and the painted gardens. In this sense the quality of the herbals produced by Sabbati was extraordinary and remain exemplary, both of his youthful activity and of his long collaboration with the Casanatensi Dominicans.

It seems that its recurrent presence in the scientific-naturalistic documentation activity of the Casanatense passes through a common thread that, from Trionfetti to Maratti to Audiffredi, confirms that between the medicinal garden and the Dominican writing workshop there was no ideal discontinuity. The concept of a laboratory of ideas and texts, which the Libraria represented in the cultural life of the eighteenth century, expanded not in a broad sense, but in a real sense, in the awareness that science and knowledge always needed to be updated. This is how in Casanatense, splendid medieval artefacts that show us from the painted herbals to the Tacuina, alongside other unrepeatable masterpieces that are the dry gardens, reveal themselves as complementary presences. They are all testimonies of a common reality, experienced both under the experimental profile of research, and in the name of pictorial research that this reality translates into images. The editorial reproduction of volume 4460, the second volume of Sabbati’s Hortus, not only does not intend to replace the original, but will have the merit of filling the memory of that piece, unique in its kind, which cannot be duplicated. It is a praiseworthy consolation for the fracture inflicted on an organic whole that seriality, to which we have been accustomed for centuries, cannot restore.

The Roman Botanical Garden at the time of Sabbati and Audiffredi

After the premature death of Trionfetti in 1708, the Roman Botanical Garden underwent a period of oblivion until the arrival of Pope Lambertini. Benedict XIV had a “singular genius for botany” and wanted to establish two chairs, one of theoretical botany, which included “a medical professor destined to explain the virtues and use of herbs at the University”, the other of practical botany combined with the direction of the Botanical Garden. The reform also provided that the professor of practical botany could not transfer to the chair of medicine, leaving the botanical discipline vacant. The official documents were immediately followed in 1747 by the appointment of Francesco Maratti as director of the Botanical Garden. Abbot Maratti proved to be a personality of great cultural stature, as well as a profound connoisseur of the discipline he taught, so much so that he left a profound mark on the history of the Roman Garden. This was also possible thanks to another excellent figure who supported him during his academic mandate: Liberato Sabbati, appointed first custos of the Garden from 1749 to 1779. […]

Liberato Sabbati was born in Bevagna in 1714 and moved to Rome at a very young age, before the age of 17. His origins were modest and a stay in Rome could represent a decisive choice both for his cultural education and for a profitable social integration that would help him in the career he wanted to undertake.

In Rome he studied pharmacy in Marco Palilli’s apothecary in the Monti district and entered into contact with the Casanatensi Dominicans, certainly already in 1744, according to what is attested by the purchases of his works.

It is the beginning of a long-lasting collaboration that will see Sabbati as the author of his major works that are preserved in Casanatense. They are still today the clear example of how the “dry gardens” and the “painted gardens” constituted a unique baggage of botanical knowledge. In fact, they managed to combine, albeit with different didactic value, practical experience with the aesthetic taste of reproduction, as faithful as possible to the model in nature.

It is the beginning of a long-lasting collaboration that will see Sabbati as the author of his major works that are preserved in Casanatense. They are still today the clear example of how the “dry gardens” and the “painted gardens” constituted a unique baggage of botanical knowledge. In fact, they managed to combine, albeit with different didactic value, practical experience with the aesthetic taste of reproduction, as faithful as possible to the model in nature.

Sabbati, especially passionate about dry gardens, proved to be an excellent student as well as collaborator of Maratti. Between the two there is a communion of intent and exchange of professional and scientific experiences as Sabbati himself will declare in the preface of one of his precious pamphlets.

The first works of Sabbati purchased by the Casanatense prefect Agnani were L’Innesto (Ms. 1902) and the Deliciae botanicae (Ms. 3519-3521).

The Innesto is a youthful work, the fruit of his experience as a student, while the Deliciae were created before his departure for Ferrara, where he stayed for some time. The reasons for this trip remain unknown, but we know that there he published the Synopsi plantarum, considered the synthesis of the first two works. […] Most likely the Studium of Ferrara, returned to its ancient splendor thanks to the new impetus given by the papal administration, appreciated his talent and stimulated in him the desire to broaden his knowledge.

And it is precisely from Sabbati’s Ferrarese production that the strong bond with Maratti emerges, as mentioned, not yet institutional, because it preceded the appointment of custos. The disciple recognizes in Maratti the master who cured his ignorance to instill knowledge and gratitude, but with whom a scientific collaboration and assiduous research was established.

Sabbati immediately showed an enormous productive capacity, combined with an equally evident ambition, keys to his success and his fruitful activity. He created a conspicuous series of herbals that are preserved in large part in Rome in the Casanatese, Alessandrina and Corsiniana libraries […] When in 1759 Sabbati was appointed first custos of the Roman Botanical Garden of Maratti, the premises were already fully in place not only for A review of Sabbati’s herbals in the Library represents a cross-section of the life of the illustrious botanist and marks not only the continuity of production but also the economic and cultural support he received from the Dominicans and from Father Audiffredi in particular. […]

In addition to L’Innesto and Deliciae, his career, which was already well underway, was gradually commissioned and purchased over time, but for broad and long-lasting collaborations with prestigious Roman institutes, not least the Casanatense.

![]() Catalogus plantarum iuxta methodum Tournephortianum … (Mss. 1904-1905)

Catalogus plantarum iuxta methodum Tournephortianum … (Mss. 1904-1905)![]() Overall index of the Hortus Hyemalis of Trionfetti (Ms. 1670)

Overall index of the Hortus Hyemalis of Trionfetti (Ms. 1670)![]() Theatrum botanicum romanum … (Ms. 1903)

Theatrum botanicum romanum … (Ms. 1903)![]() Hortus romanus iuxta systema Tournephortianum … (Mss.4459-4463)

Hortus romanus iuxta systema Tournephortianum … (Mss.4459-4463)![]() Selectarum plantarum Horti Botanici Romani Icones ad vivum delineatae et nativis coloribus distinctae ad usum Bibliothecae Casanatensis... (CCC.O.II.9) […]

Selectarum plantarum Horti Botanici Romani Icones ad vivum delineatae et nativis coloribus distinctae ad usum Bibliothecae Casanatensis... (CCC.O.II.9) […]

It is quite evident that the credentials that Sabbati enjoyed in the academic environment, the long attendance of the Library since he was a young student, the partnership with Maratti, contributed to convince the prefect Audiffredi to invest a considerable amount of capital for the realization of these works, in particular for the Icones, with a very high final cost. His intention was to make them the Herbarium of Casanatense as a tangible testimony of a long and fruitful collaboration.

The Hortus Romanus by Liberato Sabbati (v. II of Ms. 4460)

The Hortus Romanus by Liberato Sabbati (v. II of Ms. 4460)