by Sabina Fiorenzi

When the Tevere was scary.

When the Tevere was scary.

Since ancient times, the Tevere has been a ‘cross and delight’ for the inhabitants of Rome and its surroundings. The amenity of its banks and the pleasantness of the activities that could be exercised on them and on the water were in fact periodically contrasted by frightful floods with terrible consequences in terms of loss of life and economic activity.

The fact that there was a familiarity with such tragedies certainly did not diminish their calamitous scope, and scholars have always applied themselves in various ways to analysing the situation and elaborating proposals capable of providing a definitive remedy to the problem of catastrophic flooding of the Tiber. In ancient Rome, for example, even Pliny the Elder reflected on these events and, in a passage of his Naturalis historia, saw the Romans’ lack of religiosity as the cause of the river’s floods, and as a remedy a greater number of sacrifices to ingratiate themselves with the gods and ward off punishments in the form of natural disasters.

Since the mournful recent events caused by the overflowing of rivers and torrents have once again sadly brought to the fore the problem of the care and maintenance of watercourses and the territory in our country, we decided to propose to our readers a selection of works dealing with the problem of the Tiber floods, carried out and commented on by three colleagues: Ada Corongiu, Antonietta Amicarelli Scalisi and Rita De Filippi. This work was carried out for an exhibition entitled Roma la città dell’acqua (Rome, the city of water), set up in the Casanatense back in 1994. Many years ago then, but it seems to us that the careful selection that was made for that occasion among the library’s ancient books still retains all the validity of well-done and exhaustive research on a subject.

We firmly believe that preserving and making available to all citizens of today and tomorrow the historical memory of events, the problems associated with them, and the theoretical reflections from which they arose and which they generated can contribute to the growth and improvement of society as a whole. This is why libraries and archives were established and why, in our opinion, they should continue to exist.

We dedicate this editorial to remembering the victims of the recent floods in many, too many Italian regions.

In order to introduce the part of the catalogue of that ‘94 exhibition dealing with the flooding of the Tiber, we have chosen in particular the illustrative commentary of four works, among the many of fundamental importance on the subject in question, the fruit of different approaches to the same problem: the first by Francesco Maria Onorati: Apologia … per la passonata fatta sopra il Tevere fuora di Porta del Popolo in difesa della strada Flaminia con la direttione del signor Cornelio Meyer famoso ingegniere olandese … Rome, 1698, in which the author magnifies the realisation of the project to restore and contain the river by the Dutch engineer Cornelis Meyer.

In order to introduce the part of the catalogue of that ‘94 exhibition dealing with the flooding of the Tiber, we have chosen in particular the illustrative commentary of four works, among the many of fundamental importance on the subject in question, the fruit of different approaches to the same problem: the first by Francesco Maria Onorati: Apologia … per la passonata fatta sopra il Tevere fuora di Porta del Popolo in difesa della strada Flaminia con la direttione del signor Cornelio Meyer famoso ingegniere olandese … Rome, 1698, in which the author magnifies the realisation of the project to restore and contain the river by the Dutch engineer Cornelis Meyer.

The second, by the architect Carlo Fontana: Discorso … sopra le cause delle inondazioni del Teuere antiche e moderne à danno della città di Roma, e della insussistente passonata fatta auanti la villa di Papa Giulio III… Rome, 1696, in which the famous architect challenges the validity of the ‘Meyer operation’ in favour of his own project.

The third, the important work by engineers Andrea Chiesa and Bernardo Gambarini: Delle cagioni e’ de rimedi delle inondazioni del Tevere. Della somma difficoltà d’introdurre una felice, e stabile navigazione da Ponte Nuovo sotto Perugia sino alla foce della Nera nel Tevere, e del modo di renderelo navigabile dentro Roma, 1746.

And finally the fourth and last, by Luigi Amadei: Progetto della deviviazione del Tevere del generale Giuseppe Garibaldi … Naples, 1875, which is one of a large number of proposals that were never realised, but which is nevertheless useful both because it illustrates Garibaldi’s project to deviate the Tiber, commissioned by the general, and because it also contains the narration of the political-administrative events that preceded the start of the much-dreamed of solution to the Tiber problem, which then took place according to the project of engineer Raffaele Canevari, also illustrated in the publication.

It goes without saying that these notes serve solely to introduce the subject and to arouse the reader’s curiosity and the scholar’s interest: for further study, please refer to the list of works and their bibliographical entries, but above all to the original texts described in them, all of which can be found in the library.

Francesco Maria ONORATI

Francesco Maria ONORATI

Apologia … per la passonata fatta sopra il Tevere fuora di Porta del Popolo in difesa della strada Flaminia con la direttione del signor Cornelio Meyer famoso ingegniere olandese … In Rome, Per il Bernabò, 1698. [8], 59 p. ill., 1 fold-out fol. table (30 cm)

(coll. Misc. 205.11)

After dedicating this Apologia to Cardinal Giovanni Francesco Albani, Secretary of the Bills of Innocent XI, Onorati addresses the reader as follows: ‘The passonata directed by Sig. The passonata directed by Mr. Cornelio Meyer, a Dutch engineer, has had so many oppositions that it has been more annoying to overcome them than to do the work, but finally, having been recognised by the first Courts of the Court as insubstantial, the passonata has been approved, & today happily unharmed, & intact notwithstanding the many floods of the Tiber, which the greater they have been, the more they have corroborated it with a total silting up on the inner side, and with having established the riverbed as a scarp in front of it, so that the spirit, or rather the strand of the waters flows very far from the foot of the passonata. I have had the honour of representing the reasons to these supreme judges suggested to me by Mr Cornelius, according to his new principles of making ‘passonate’ according to the Dutch custom, which in those parts support with incomparable artifice on the back of the passonate the weight of all the waters of that great sea that bathes Holland…’.

As can be seen, it is a defence, made with firmness and irony, against the ‘professors’ who opposed the work done by Meyer on the Tiber, near Julius III’s villa on the Flaminian Way, where great corrosion due to a tortuous riverbed had ‘devoured’ many vines and threatened the beautiful consular road. Onorati retraces the history of the various projects that from the pontificate of Alexander VII to that of Clement X were presented and rejected because of their ineffectiveness, such as that of Ippolito Negrisoli from Ferrara, or because of their excessive price (80,000 scudi), such as that of ‘cav. Bernini, phoenix of our times.’ Until in 1675, when he came to Rome for the Holy Year, Meyer had the opportunity to confirm the truthfulness of his reputation as a water engineer by presenting, at the request of Pope Clement VII, a project to solve the aforementioned problem of the corrosion of the river near the Flaminia, at the cost of 8,000 scudi, which convinced the Sacred Congregation of the Ripe and that of the Counts.

However, during the construction, which took place under Innocent XI, ‘in addition to the natural difficulties of contrasting two very powerful elements, water and earth, the engineer had much greater difficulties caused either by emulators or by the ignorant…’ who, with false reports of collapses or negative reports on the effectiveness of the palisade, succeeded in having the funding and therefore the work suspended several times. Agostino Martinelli, who had previously publicly praised Meyer and copied his techniques, and many other architects, especially the famous Carlo Fontana who even wanted to demolish the work, stood out in this: Onorati gives us a precise account of all the disputes, provides expense accounts, describes the long realisation of the work, highlighting its merits and its perfect success and usefulness, and defends engineer Meyer from every accusation, praising ‘… the singular study, both his own and that of his two sons: continually on the lookout day and night, exposed to not a few dangers, and in particular with the Engineer having fallen several times into the Tiber in his clothes, where he once lost a diamond of 300 sc. & a clock of great esteem, & to these dangers were added the bad weather of the air in going in summer and winter through the countryside to look for stones, and bundles, and timbers, and to speed up the workmen…’. Thus, through Meyer’s indefatigable diligence, the palisade was completed, fortified by a large willow grove and many trees with firm roots. An edict of 15 March 1679 closed all controversies and decreed, against all detractors and detractors, the preservation of the work and its untouchability. (Ada Corongiu)

Carlo FONTANA

Carlo FONTANA

Discourse … sopra le cause delle inondazioni del Teuere antiche e moderne à danno della città di Roma, e della insussistente passonata fatta auanti la villa di Papa Giulio III. Per riparo della via Flaminia … In Rome, Nella Stamperia della Reu. Camera Apostolica, 1696. 35 p. 3 folding fol. tables (30 cm)

(coll. Vol. Misc. 219.9)

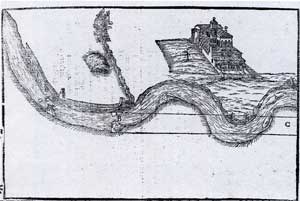

‘The esteem in which the Romans held our Tiber was so great that their blindness came to deify it …’. With these words, the famous architect begins his speech on the Tiber, which, however, is all aimed at getting to his real purpose: the attack on the work, mentioned in the title, by Cornelius Meyer, a Dutch engineer, as we shall see later. Augustus instituted the office of Magistrate for the care of the Tiber and its banks; at the time of the Republic, censors and curators were in charge of it, also assisted by a magistrate for the superintendence of the Cloaches, who saw to it that the Cloaches did not introduce materials into the river that could raise the riverbed and facilitate flooding, given its width and the shallowness of the banks. With the decline of the power of Rome, which had also enriched itself by trafficking along its river, and after centuries of neglect, the state of the Tiber, as Fontana describes it, is deplorable and its navigability almost completely compromised. The main causes of the floods he indicates are the chain of bridges (from Ponte Milvio outside Porta del Popolo, to Ponte S. Angelo, to the remains of the Ponte Trionfale (or Vatican), to Ponte Sisto (or Gianicolense), to Ponte Cestio, Ponte Palatino (or Rotto), Ponte Sublicio after the Marmorata, near the Ripa and the landing of ships); the neglected banks and above all the inequality of the riverbed, the palisades of the millers, who deviate the course of the water with them to increase and unite the currents for the service of their mills, the rubbish that at the Penna and throughout the city has raised the riverbed, and ‘. .. the augmented evils … because of the passonata subsequently described …’.

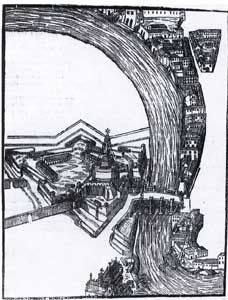

And here Fontana finally touches upon the central point of his discourse by talking about the origin and history of this work in the river. At the time of Alexander VII, a serious corrosion of the left bank of the Tiber appeared upstream of the city, which, at the height of the vineyard of Pope Julius III’s villa, put the Via Flaminia in serious danger. When Alexander VII died, the new pope Clement IX consulted various specialists for suitable remedies and, on the advice of Giulio Cesare Nigrelli, the Ferrara-born Ippolito Negrisoli, an expert on flooding in the Po Valley, was summoned to Rome. The late and inconsistent proposals of these earned Fontana the assignment to assist him in the exact delineation of the river. At the end of this survey, Negrisoli’s project was rejected and Fontana’s project was approved instead by Bernini and Agostino Martinelli, who also published edicts. But the start of the project was halted by the death of the pontiff. To his successor, Clement X, Cardinal Azzolini presented the Dutchman Cornelio Meyer, who, according to A., was able to win the hearts of the high prelates by making them believe that he could use completely original and economical systems. Fontana’s project, consisting of a system of obtuse angled passages, with groynes and fortifications on the opposite bank to channel the current, was rejected and the work entrusted to Meyer. One can understand the architect’s dismay … Meyer’s project, which was based on the fact that the corrosion depended on the diagonal buoyancy of the water discharging from the alluvium opposite the corroded bank, involved the construction of a groove at the beginning of the bend and four others of a single line of piling towards the alluvium to facilitate the flow of water towards the centre of the river, the excavation of a channel, and the construction of a large piling in the river, the cutting of large parts of land on the opposite bank to widen the course.

When work began in 1678, criticism, perhaps somewhat justified, and all kinds of boycotts were unleashed. In 1684, at a particularly critical moment, an expert report was commissioned from Fontana, who took the opportunity to completely rebuke Meyer’s work, which, in his opinion, had to be destroyed, and to reintroduce his wall-building project. But once again his project remained on paper and in 1699 an edict was issued for the preservation of the passonata.

The publication contains Fontana’s plans and expertise on this controversial matter and is accompanied by 3 beautiful engraved plates entitled: 1) The state of the river in time of corrosion. Modo proposto per il rimedio; 2) Profilo del Tevere con passonata; 3) Situazione del Tevere a Ponte Molle.

Pages 31-35 contain a ‘Discorso di monsig. illustriss. Vespignani sopra il Tevere e qual rimedio possa darsi per diminuire in parte l’inondazioni … . (Ada Corongiu)

Andrea CHIESA – Bernardo GAMBARINI

Andrea CHIESA – Bernardo GAMBARINI

Delle cagioni e’ de rimedi delle inondazioni del Tevere. Della somma difficoltà d’introdurre una felice, e stabile navigazione da Ponte Nuovo sotto Perugia sino alla foce della Nera nel Tevere, e del modo di renderlo navigabile dentro Roma. In Rome, Nella Stamperia di Antonio de’ Rossi, 1746. 119, [1] p. ill., 2 fold-out fol. plates (43 cm) (coll. C.IV.9)

In the anonymous preface to this famous work, it is recalled that Jacomo Castiglione counted thirty-six major floods in Rome from its foundation to 1598 and that many other serious ones, testified to by the various inscriptions scattered around the city, followed since then. After the umpteenth flooding of the Tiber in 1742 and the usual sad sequel of deaths of people and animals, ruins all over the city and the inevitable diatribes on the true causes of the phenomenon, towards the end of the following year, Pope Benedict XIV called two of his fellow countrymen to Rome, the Bolognese engineers Andrea Chiesa and Bernardo Gambarini to clarify the state of things and propose possible remedies: ‘. …And they quickly set to work, neither by the boredom of fatigue, nor by the danger of unhealthy air in the hot season, delayed in a few months to perfection, and then reduced them to profiles and maps, and in two reports they declared them in detail, one of which belongs to the visit of the Chiane, the other to the state, & adjacencies of the Tiber. The pope’s interest was also directed to the urban and extra-urban navigation of the river, but both for this problem and that of flooding, the reports of the two engineers did not leave much hope, limiting themselves rather to the ascertainment of the enormous difficulties and unsustainable costs of works that, if not useless, were certainly only palliative.

The first report describes the meticulous sounding of the riverbed and reconnaissance of the banks along the entire course of the river. In it, the identification of the main causes of the floods within the city is the same as that of many other authors, and even ‘…the remedies to keep floods down and prevent some of the smallest floods…’ are precisely non-resolutive and do not differ from those of Bacci, Castiglione and many others. They consisted in removing the remains of the ancient Sublicio and Trionfale bridges and of other walls and buildings crumbling in the water; in transporting the albeit useful water millstones upstream, outside the city, freeing the river of their palisades so harmful to the free flow of the current; in freeing the bridges from all deposits of earth and other materials created behind their structures; in removing also a small island formed at the beginning of the two branches that form the Tiberina island. Gambarini and Chiesa give many suggestions for carrying out these operations, while on p. 51-52 they define them as ‘… placed towards the edge of the impossible …’ or ‘… of … excessive expense …’ more substantial interventions such as the creation of large embankments (muraglioni), collectors for the water from the “chiaviche”, and “drizzagni”, i.e. straightening of elbows that were too narrow in the river’s course.

Only engineer Gambarini signed the second report, dedicated to the Chiane (the fork of the river of the same name in Tuscany before entering the Paglia and then the Tiber) so many times and by so many authors considered to be one of the main causes of the disastrous floods of the river outside and inside Rome. The Bolognese engineer maintains and demonstrates that the reclamation works in that place, the cause of so many quarrels between Florence and Rome, had no negative effects and that the Chiane water cannot therefore be the cause of the Tiber floods. On the problem of the possibility of restoring a stable navigability between Perugia and the confluence of the Nera in the Tiber, the volume contains the report of the visit made in those places, commissioned by Clement XII, by Giovanni Bottari and Eustachio Manfredi, who conclude: ‘… so that to consider well what we propose rather than encourage to undertake this navigation, may perhaps serve to depose for ever in the future the diligence, and the thought.

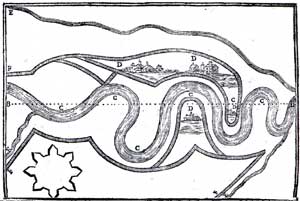

Finally, a report signed by Chiesa alone deals with how to make the city section of the Tiber between Ripetta and Ripa Grande navigable, now traversed almost only by small boats. The causes that make navigation difficult or impossible are indicated as the low height of the water, the excessive slope of the riverbed, numerous obstructions that clutter it such as ruins, palisades, and the mills, especially those under the ghetto and the one near Ponte Rotto. On the whole, despite the detailed remedies suggested, the author does not seem very convinced of their efficacy and cost-effectiveness. From what has been mentioned above, it is clear that even Gambarini and Chiesa’s ideas were not able to solve anything about the age-old problem of the Tiber, but what made their work memorable are the surveys, carried out by them with great precision and commitment, of the entire course of the river and their depiction. The publication in fact, already embellished with small engravings of views of Roman antiquities, is accompanied by two very large folding plates that give an exact description of the state of the river in the mid 18th century, with everything in it, on it and beside it.

The first (167 x 73 cm), entitled ‘Plan of the course of the Tiber and its surroundings from the mouth of the Nera to the sea and levelling profile of the same…’ also shows, on a larger scale, views and sections of Ponte Felice, near Magliano Sabina, Ponte Molle, Ponte S. Angelo, Pontre Sisto, Ponte Quattro Capi, the façade of S. Bartolomeo all’Isola, and the view of Ponte Ferrato (Cestio).

The second (67 x 48 cm) is entitled Andamento del corso del Tevere, e sue adiacenze per il tratto della città di Roma, e profilo di livellazione, e sezioni, che comincia dal Porto di Ripetta fino al Porto di Ripa Grande per esaminare se si possa rendere navigabile questo fiume tra i sud.i Porti…

In addition, in this copy of Chiesa and Gambarini’s work there are, without being part of the edition, two other large plans, related to the Chiane, outlined by hand and also of considerable historical-documentary interest. The first, on parchment (89 x 59 cm), is in colour with gilded cartouches and coats of arms and bears the title: Pianta e profilo dello stato dell’acque delle Chiane dal Ponte Valiano fin’ al Ponte di sotto, e di lì ai Muro grosso, riscontrata con quella fatta l’anni 1663, e 1664, e ridotta al pnte stato ne mesi Maggio e Giugno 1719 da noi Egidio Maria Bordoni Ing.e per la parte di S. S.ta Giovanni Franchi Ing.e per la parte di S. A. Re.

The second, on paper (150 x 53 cm), also in colour, is entitled Pianta delle Chiane da Valiano fino al Bastione detto al Campo alla Volta e di qui fino al muro Grosso tratta dalle piante fatte, e nel 1719 dal fu Sig.r Egidio Bordoni, e nel 1724 dalli Sig.ri Bonacursi, e Facci, ridotta ed accomodata al presente stato, ritrouato il mese di Febraro del corrente nno MDCCXLIV. (Ada Corongiu)

Luigi AMADEI

Luigi AMADEI

Progetto della deviviazione del Tevere del generale Giuseppe Garibaldi compilato da Luigi Amadei… Naples, Stabilimento Tipografico di Francesco Giannini, 1875 80, [6], 9, [1], 5 p. 28 cm

(coll. Vol. Misc. 2948.4)

The long theory of books on flooding described so far has shown how the problem of the Tiber, tackled by all with passion and with the intention of finding definitive solutions, was, in reality, never resolved, despite the proclaimed commitment of so many popes and the Capitoline administration. However, the presentation of this work by engineer Amadei (retired engineer colonel, former professor of applied mechanics and former municipal and provincial councillor of Rome), which is part of the large number of proposals that were never realised, is useful both because it illustrates the Tiber diversion project devised by the general on Garibaldi’s behalf, and because it also contains the narration of the political-administrative events that preceded the launch of the much-dreamed of solution to the Tiber problem, which took place according to the project of engineer Raffaele Canevari, also a member of the Rome City Council. Raffaele Canevari, also illustrated in the publication.

This is how Amadei tells the story (p. 1 ff.): ‘The extraordinary flood of 28 December 1870, which submerged a large part of Rome, raised a universal outcry because of the many damages it caused to public health and the interests of the citizens. And I myself was a witness, as one of the Presidents of the Relief Commission on that mournful occasion, of the damage and ruin caused to the city by the flood, and in particular to the poor class, who, in addition to the assaults of poverty, had to suffer even the most violent ones of the flood in their meagre hovels. This calamity drew the government’s attention to the unhappy condition of Italy’s capital city; and the urgency of studying the important issue of the Tiber, i.e. to free Rome from its floods, was felt. The government appointed a commission of engineers who ‘…after a year of study, issued an opinion, from which the engineers Possenti and Armellini disagreed…’.

In short, the Commission approved Raffaele Canevari’s project, considering it perhaps more expensive, but also safer than Possenti’s. Amadei says that Canevari’s project ‘… can be summarised as follows:

1° In the construction of a slab at Ponte Milvio;

2° In the embankment of the Tiber, from the stones of S. Giuliano to the city;

3° In the construction of the bank walls in the urban section;

4° In giving the riverbed the width of 100 metres between the tops of the walls;

5° In the suppression of one of the branches of the Tiber at the Tiber Island;

6° In the addition of a span to Ponte S. Angelo, and in the demolition of Ponte Rotto, to be replaced by a new bridge;

7° In the removal of existing obstacles in the riverbed;

8° In the construction of two Collectors parallel to the banks;

9° In the embankment of the left bank until below S. Paolo.

That in the meantime the beginning of April 1872 be given to the removal of the obstacles that the Tiber encounters in Rome’.

In short, even if rejected, General Garibaldi’s project (which provided for the Tiber to be led from the vicinity of its confluence with the Aniene, outside the city, until it rejoined the natural riverbed halfway between S. Paolo and the mouth, while inside the city the river would continue to follow its course, but in a narrowed and rectified riverbed) finally served to obtain approval for the concrete beginning of work according to Canevari’s project with a law of July 1875. This last project, on closer inspection, identified the same causes, and proposed, albeit with enormously advanced knowledge and technical means, the same solutions already read about many times in the numerous works on the Tiber floods presented here, i.e. ‘drizzagni, muraglioni’, bridges to be destroyed or widened, embankments, diversions, canals, collectors, changes to the situation at the Tiber Island. We have seen with regard to the latter that the Canevari project foresaw, with the elimination of a branch of the river, its destruction, which, thanks to the intervention of many archaeologists and cultural figures, did not happen. It is certain, however, that the enormous works planned by the engineer required energetic and demolishing interventions, and that the reclamation of the banks and the widening of the riverbed certainly entailed a great change in the river landscape, as did the remaking of Ponte Cestio, the almost total destruction of Ponte Rotto, the silting up of the magnificent Port of Ripetta, the creation of the Tiber embankments, etc. But there is also no doubt that the problem of the Tiber flooding in the city was finally solved, even if at the sacrifice of so many historical testimonies of ancient and papal Rome. (Ada Corongiu)

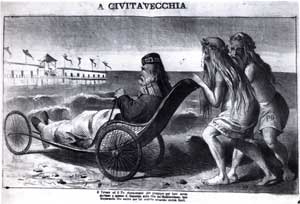

The pictures illustrating the editorial are taken from F.M. Bonini Il Tevere incatenato… Rome, 1623 and from La Capitale, a. 6 (Jan-Jun 1875)

When the Tevere was scary.

When the Tevere was scary.